How Subway Ads Direct NYC Straphangers, a photo essay

Master’s Program, Evolution of Writing

In the New York City area, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) is tasked with transporting roughly 5.4 million commuters in, out, and around the city on its subway transit system during the average weekday (Subway Ridership at a Glance). In total, the MTA network services a 5,000-square-mile area that spans New York City, Long Island, southeastern New York State, and Connecticut—it is the largest transit system in North America (The MTA Network).

Connecting the boroughs of Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx are 27 train lines and 6,435 individual subway cars (The MTA Network). Within these subway cars, at any given time, are an estimated 40 advertisements or advertising spaces. That means, on the average weekday commute, approximately 257,400 ads have the potential to be shown to 5.4 million riders.

And people think the skyline is impressive.

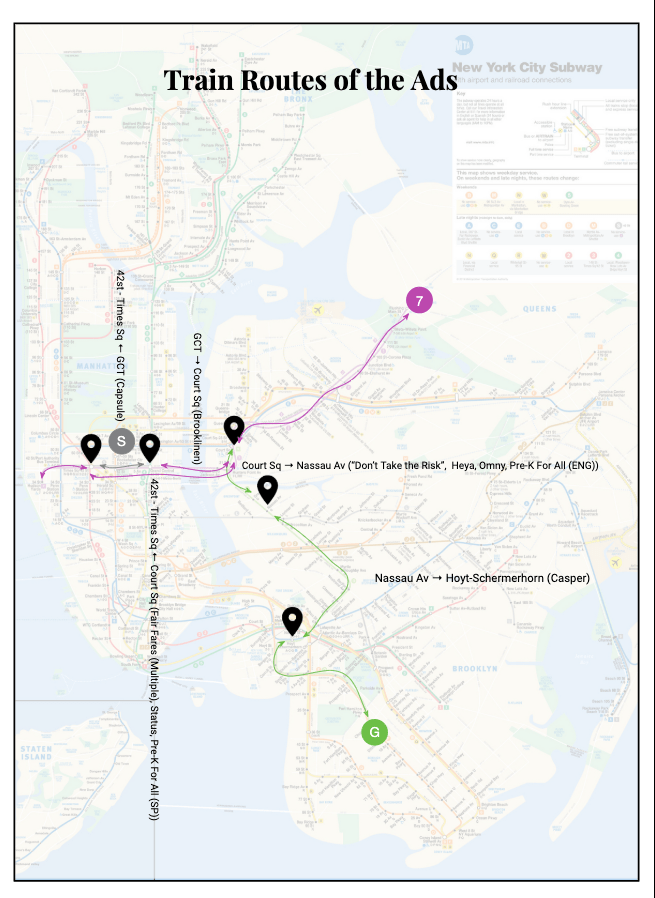

In the following photos is a captured sampling of subway ads running in and between Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan—New York City’s largest boroughs, with Brooklyn boasting of 2.6 million people, Queens of 2.3 million, and Manhattan of 1.6 million (USA: New York City Boroughs). In the brimming petri dish that is New York City, subway ads are a distinct representation of the cultural messaging that directs its 5.4 million subway riders to keep it moving. However, how these ads use writing to direct riders-as-readers varies based on whether the messaging is product messaging or public messaging.

And for all the routes and riders, trains and stations, companies and campaigns, all subway ads are essentially distilled into these two types of messaging with one destination: the reader. This Barthesian reader is a destination on which language as a performance can converge in all its multiplicities. And, as showcased in subway advertising, even text that lacks, well, text still contains dialogue that engages and language that acts—or, in these cases specifically, directs.

Like the MTA officers instructing crowds to “Let ‘em off, let ‘em off” as commuters detrain, the famous “Stand clear of the closing doors, please” announcement, and train conductors informing riders that “this is [garbled] stop, next stop will be [also garbled]”, New York City subway ads are just as reflective—and directive—of the city as the silver subway cars themselves.

As it relates to subway ads, product messaging tends to strive for uniqueness or cleverness. Typically, this involves a complex form of humor: a play on words, puns, idioms, local jokes, and special formatting. In other words, in a city teeming with (literal and figurative) noise, what will make your message stand out to the reader above all others?

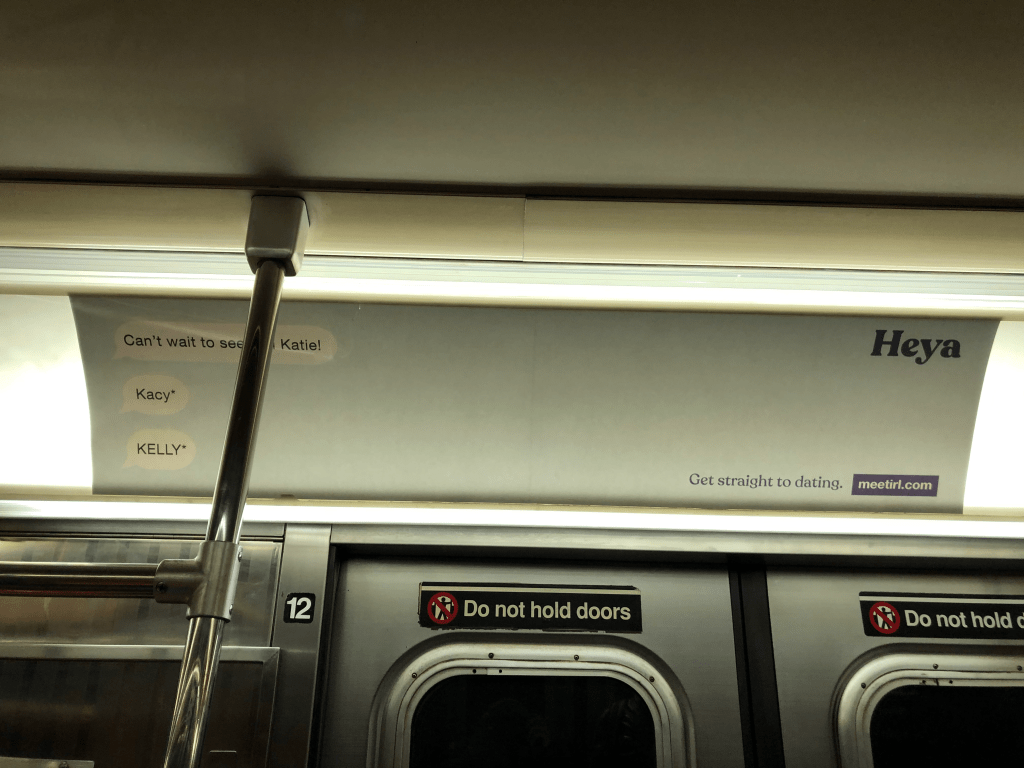

Ads like Capsule and Heya, for instance, adopt a chatbox-style of writing to reflect a common way in which commuters (especially those on their phone) use and encounter writing. Heya succinctly captures the humourous frustration of autocorrect and trying to date in New York City; they suggest the reader “get straight to dating” and include their URL as the suggested place to do so. Capsule also attempts to find the funny in common frustrations, like dealing with insurance companies or trying to find a pharmacist—human or otherwise.

(Note: in the two photographed Capsule ads, there is no overt ‘location’, but subway ad campaigns, like this one, often run multiple ads lengthwise down the train car and could be located further down. Regardless, the ads do display Capsule’s name and branding fairly obviously for readers.)

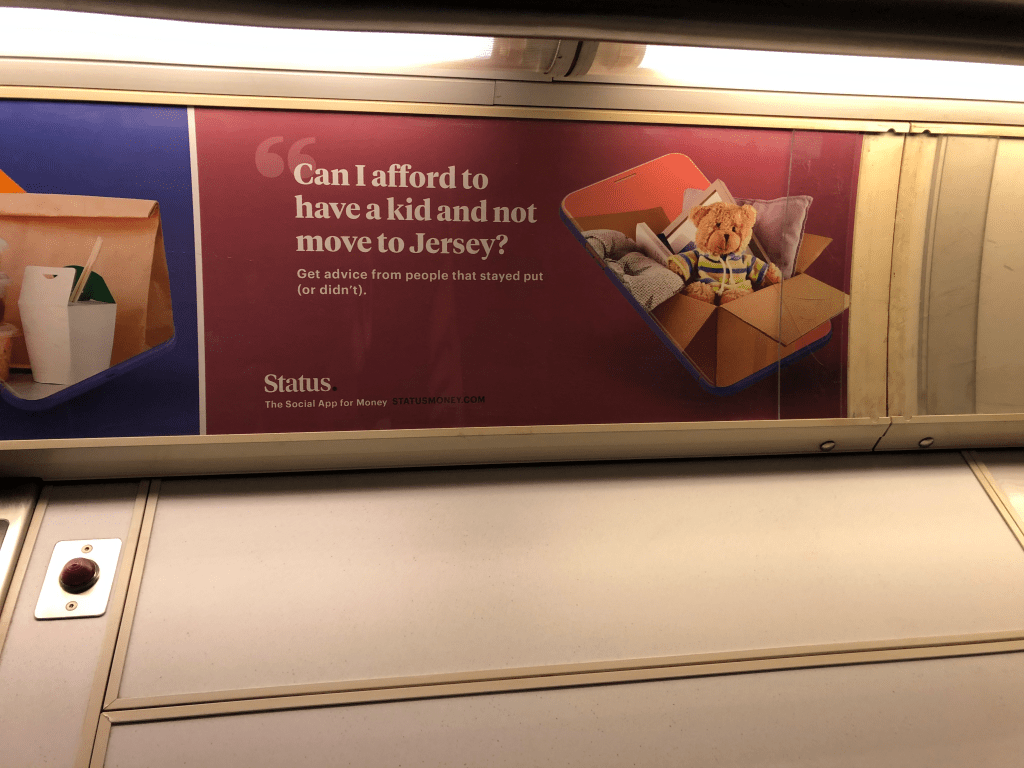

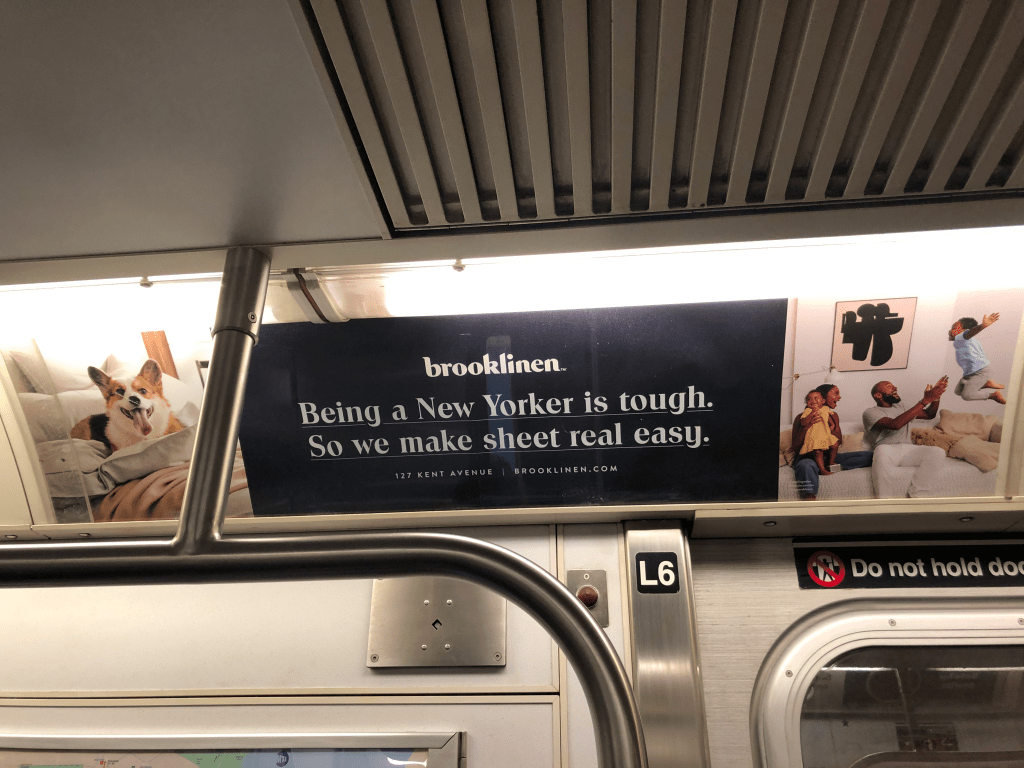

Companies like Brooklinen and Status use New York-specific humor and stereotypes as their attempt to stand out to readers (the “tough New Yorker” and the fear of having to move to New Jersey, respectively). Brooklinen, in addition to a sleek “sheet” pun, includes their physical and digital address. Status, in their own slick move, embeds the word “app” into their tagline and includes their web address: a two-for-one digital direction drop. Readers who are moved to action by this copy simply need use the phone likely in their hand to check out the app or place an order.

And finally, a brand so infamous for their subway ads that you can hear New Yorkers across the city collectively groan when you mention them in conversation—Casper.

In a brilliant grasp of a ‘captive audience’, Casper subway advertisers took common sleep idioms and puns and transformed them into word puzzles (or, “puzzzles”, as Casper calls them) that make already-frustrated New Yorkers even more frustrated.

To mitigate the outrage, Casper directs readers to its website (casper.com/puzzzles)—a place where readers can finally figure out a “puzzzle” solution (and drive up Casper’s website traffic at the same time). Truly, if “unique” or “clever” is the hallmark of product marketing in the New York City subway cars, Casper is king.

In public messaging, writing directed towards New York City’s community has its work cut out for itself. Deceptively simple and concise, the messaging needs to be easily translatable and informative for a diverse, multilingual readership. If product messaging asks: “What will make our message stand out to readers?”, then public messaging asks: “What will make our message be understood by readers?”

It comes as no shock that the MTA uses its own real estate to deliver relevant messages. The first two ads advertise Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Fair Fares initiative, a community measure that allows eligible applicants to receive a 50% discount on subway fares. The captured ads showcase how the same ad is displayed in different languages: the first ad is written in Chinese; the second in Spanish. The ads serve to inform its readers about the initiative and provide them a location in which to find out more: a website, a 311 number, and a Twitter hashtag, collectively.

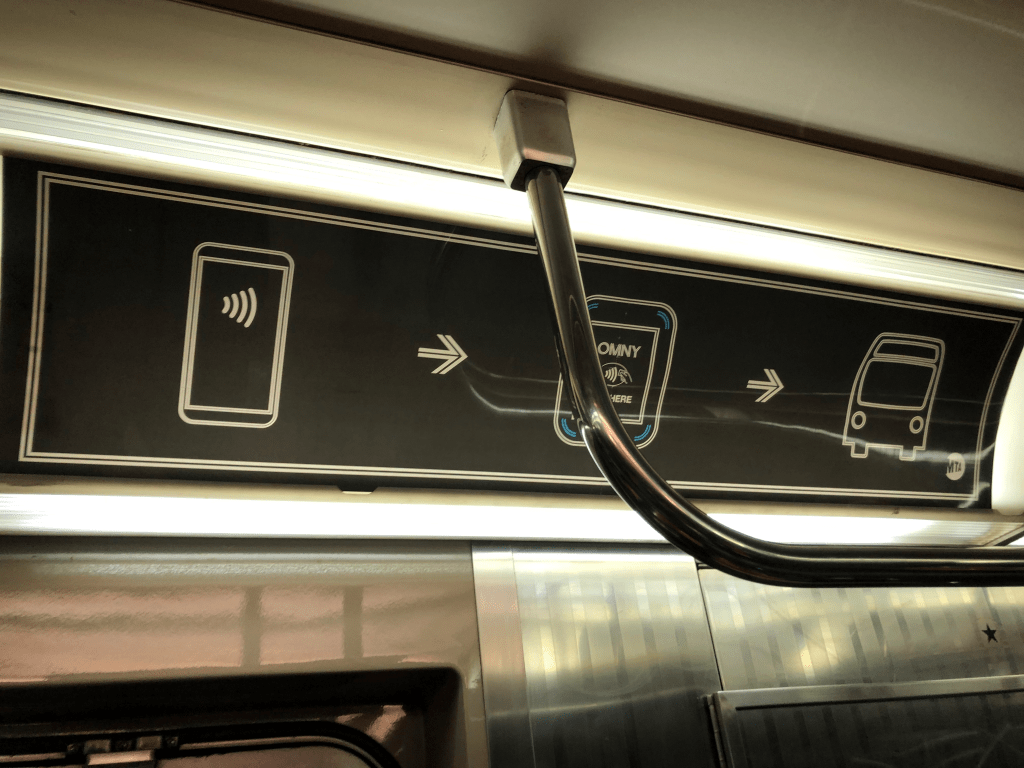

In MTA’s OMNY ad, they promote another community initiative: the overhaul of their fare system (from physical MetroCards) to a more modern contactless fare payment system.

Perhaps in line with their effort to be more modern—or a tacit understanding of their multilingual readership—the ad uses only iconography to communicate its message and direct readers to the OMNY app.

Interestingly, most stations along the route in which this was promoted—the G train line running from South Brooklyn to Queens—do not currently have OMNY-capable subway entrances. To be fair, trains sometimes run over different lines on the weekend (i.e. a train that normally runs on the F line might run as a G train over the weekend), and this could be the case here.

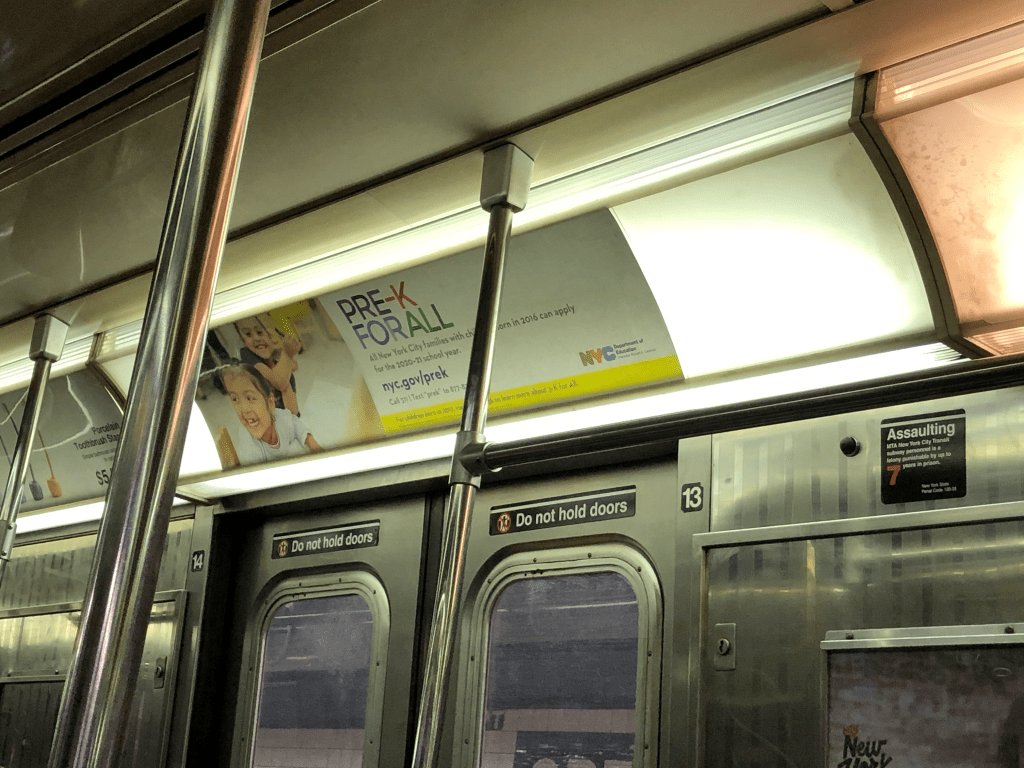

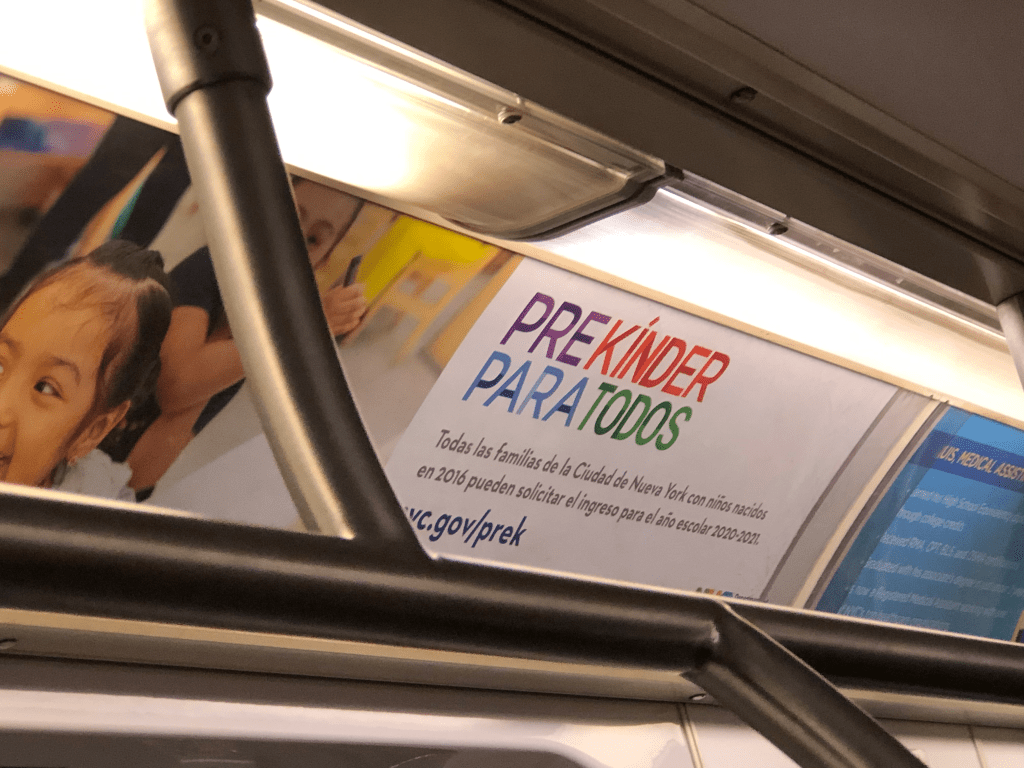

Pre-K for All ads are also shown in multiple languages. Their two photographed ads here (in English and Spanish) aim to provide pertinent information concisely and in multiple languages. The messages offer three directions in which readers can go: call 311, a text number, and a website. (Note: The subway bar is blocking this portion in the Spanish version of the ad.)

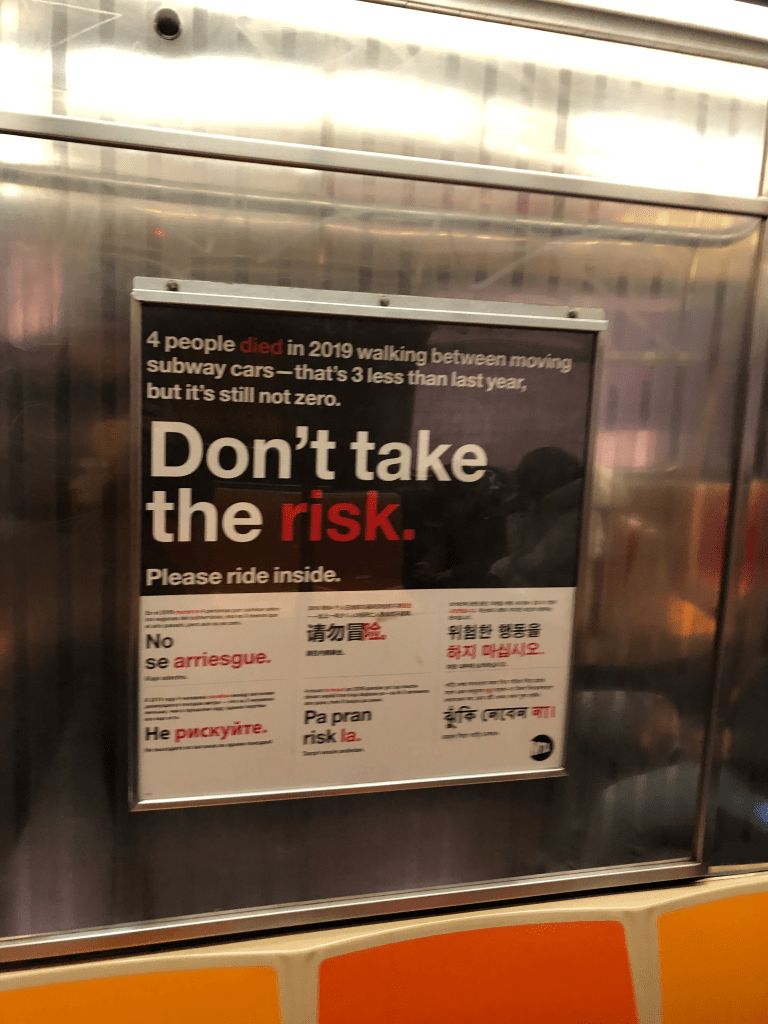

Finally, in one last MTA public directive, they encourage readers to “not take the risk” of walking between subway cars. Keeping in theme with other public messages, it is concise, direct, informative, and translated into 6 languages below the larger English message. There is no website, app, call line, or chat number. This ad directs you to stay exactly where you already are: inside.

Combined, the nine ads in this essay alone ran through three boroughs with a collective population of 6.5 million and had the potential to infiltrate 5.4 million lives in a single day, without ever having to, God forbid, go to Jersey.

Symbolic of the city itself: subway ads are a directive force compelling readers to their next destination while also servicing readers as a destination. Product messaging attempts to direct its readers with artful entertainment—be it a local joke, a clever pun, or a form of branded uniqueness. Public messaging strives to direct its readers with directness, compelling passengers with straightforward, concise, multilingual missives—though, that in and of itself is an art form.

New York City, down to its subway advertisements, is a cultural ecosystem of directions and destinations. Whether it’s making sure you have access to affordable public transportation, education, health insurance, fancy bed sheets, or a date for Friday night, subway ads are a distinct marker of the New York City way: a guarantee, more certain than your train being on time, that someone or something will always be there to tell you what to do, where to go, how to get there, and to—above all else—stand clear of the closing doors, please.