A Lexical History, Master’s Program, Linguistics & Writing

“Let me explain something to you. I am not Mr. Lebowski. You’re Mr. Lebowski. I’m the Dude. So that’s what you call me. You know, that or, uh, His Dudeness, or uh, Duder, or El Duderino if you’re not into the whole brevity thing.”

For over three centuries, the word dude has persisted in the immeasurable world of language. Investigating the lexical history of dude presents a fascinating linguistic evolution from old rags to fashionable, from outsider to insider, from a group address to a vocal tic. Further, exploring dude’s lexical history opens an entryway to exploring how language encapsulates social relationships and identity. Using research from Robert E. Knoll, Richard A. Hill, and Scott F. Kiesling, one can investigate the linguistic, social, and cultural changes dude undergoes over time and, using research from Stephen J. Clancy, compare its linguistic, social, and cultural durability in the American English language to a similar “quasi-genderless” group address, guy.

Dude, What’s Your Story?

Robert Knoll explores several of dude’s potential stories of origin in his article, “The Meanings and Suggested Etymologies of ‘Dude’”. These hypotheses range from W.W. Skeat’s suggestion that dude comes from the German duden-dop (a blockhead); Alfred Nutt’s suggestion of the German dutt or dutte; or Professor Charles Bundy Wilson’s connection to the Portuguese duodo, meaning a simpleton or fool (Knoll 21). Yet, none of these theories account for the original fashionable roots of dude, and by the 1990s, scholars adopt a much more precise origin of dude—one Hill labels a “rag-to-riches” tale in his article, “You’ve Come a Long Way, Dude: A History” (321). Hill’s etymological research suggests dude first appears as duddes in the 8th century, a term for clothing. A variation of duddes (now dudes) appears in the 15th century as a term specifically reserved for old rags; dudesman also appears as a term referring to a scarecrow, likely dressed in the old rags (Hill 321). This theory is also supported in Kiesling’s study, “Dude” (282). Thus, by the last quarter of the 19th century, Hill states it is widely agreed upon by scholars that dude is now synonymous with “dandy”, meaning a “well-dressed man” (321). This definition of dude continues throughout the first half of the 20th century, until the First Great Dude Shift (Hill 321).

Hill posits the First Great Dude Shift as when the definition of dude begins referring to both a “sharp dresser” and an “outsider”. This is a noticeable shift away from dude as fully synonymous with dandy. Hill notes one poet’s semantical distinction between dandy and dude:

I’m a dandy I’ll have you know,

With the ladies I’m never rude;

this style is all my own,

With it I carry tone,

I’m a dandy but I’m no dude.

(Barrere and Leland, as cited in Hill 322)

This difference in connotation aligns with Hill’s suggestion that the First Great Dude Shift involves a merging of dude as both a sharp dresser and one who “carries the taint of ‘outsider’ or ‘uninitiated’” (321). The “sharp dresser-outsider” connotation also emerges in Knoll’s students’ notion of a dude as a tourist:

My students also inform me that though they use the word almost exclusively as it refers to tourists on ranches, their elders use the term more broadly to mean any kind of fop, any person who overdresses, whatever his origin and present geographic location. (Knoll 20)

It appears the “outsider” connotation derives from the notion of one being overly-dressed and thus, discernible as an outsider from the crowd or a tourist from the locals.

By the 1930s and 1940s, however, the outsider/tourist connotation of dude begins to shift. According to Hill, during this time Mexican Americans who called themselves pachuchos and African Americans who called themselves zoot suiters begin adopting the term dude to refer to their in-groups. This adoption signals Hill’s Second Great Dude Shift—dude as “synonymous with fellow males in a particular group” (323). Stigmatized and marginalized groups adopt dude to mean “one of us” and thus marks the shift of dude from outsider to insider. This shift is critical because not only does it begin dude’s use as a general address for a group, it also marks the beginning of dude as an all-purpose synonym for guy (Hill 323). However, Stephen J. Clancy in “The Ascent of Guy” suggests that dude does not have the same capability as guy, where guy is a “new generic noun…that has peripheral meanings that include people of both genders” (284). He argues that nouns like dude (and man) are not competitors for a masculine-referent-turned-quasi-genderless term of address:

Words like man and dude have long served as exclamations, not really forms of address, or even as specifically masculine referents. Man, it’s cold! or Dude, that’s great! could be part of any colloquial utterance, whether or not one or both speakers or addressees were male. (Clancy 287)

However, both Kiesling’s and Knoll’s research shows quite the opposite. In 1952, Knoll’s published paper on dude reveals it already possesses the capability to refer to or address women: “Nor do my students believe that a dude must be a man, for a city woman as well as her husband can be a dude” (20). In 2004, Kiesling’s published study finds that “young women also used the term a significant amount, particularly when speaking to other women” (284). Thus, while Clancy argues for the genderless potential of guy, dude demonstrates established effectiveness amongst all genders as an address from the mid-20th to the early 21st century.

Despite its early mixed-gender usage, dude did not see its first real surge in popularity until the 1950s saw the invention of the home television. Importantly, television entered the homes of American children who were able to watch Howdy Doody, a television program which Hill suggests was a “major catalyst for the modern phenomenon of dude” (324). These children, Hill argues, grew up watching Howdy Doody and brought terms like cowabunga and dude from the “last wave of nostalgia for the Old West” to the (literal) waves of the 1960s surfer culture as teenagers (324). The surfer or beach culture of the 1960s saw a significant increase of “surf slang terms like bitchin’, twitchin’, cowabunga, and dude [that] were nearly universal among youth” (324). Thus, Hill concludes, the Second Great Dude Shift ends. With dude’s universal usage amongst American youth culture from different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, it sheds its fashionable tourist roots and becomes a general, quasi-genderless address for a group. Like Hill, Kiesling accredits the growth of dude to the American youth’s fixation on nonconformity and rejection of authority, a key component of the surfer subculture that finds its way to the 1980s (299). It is in the 1980s, which Hill labels the Third Great Dude Shift, where dude sees true evolution (325).

Dude, Where Are You Now?

In Hill’s Third Great Dude Shift, one finds much of the linguistic innovation of dude still active today. Hill notes that dude evolves to not only be a general term of address but also an exclamation of delight, affection, surprise, anger, and disappointment (325). Kiesling further explores this evolution of dude as it develops from a general address term of the 1980s to how it indexes “cool solidarity” as a stance of nonchalant camaraderie in 2004 (282). Further, Kiesling’s investigation into the ways in which women use dude in women-women interactions shows dude beginning to lose its masculine-referent nature and shift towards a genderless stance on camaraderie and nonchalance:

Dude thus carries indexicalities of both solidarity (camaraderie) and distance (nonintimacy) and can be deployed to create both of these kinds of stance, separately or together. This combined stance is what I call cool solidarity. The expansion of the use of dude to women is thus based on its usefulness in indexing this stance, separate from its associations with masculinity. Dude is clearly used most by young, European American men and thus also likely indexes membership in this identity category. But by closely investigating women’s use of the term, the separation between the first-order stance index (cool solidarity) and the second-order group-identity index (men) becomes evident. (286)

As a result of this cool solidarity, dude expands in its ability to convey emotion, agreement, social relationship, and identity. Kiesling’s research finds five specific functions for dude in social interactions: (1) marking discourse structure to reset narrative disfluency and build involvement, (2) exclamation, (3) confrontation stance mitigation, (4) marking affiliation and connection, and (5) signaling agreement (291). Thus, this first-order stance index of cool solidarity allows dude the ability to navigate social interactions and identity among varying contexts between same and mixed-gender groups of men and women.

Currently, a cursory investigation shows no signs of dude slowing down through the early 2000s. Using Google’s Ngram Viewer (an online, searchable text corpus from 1500-2008 that charts the frequency of a selected or a selection of word(s)), dude sees a continued growth from the 1700s through 2008 (see fig.1).

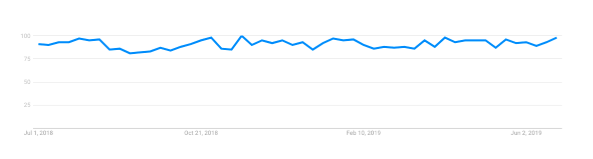

The years from 1500-1699 are not present due to a lack of texts available from the time period from which accurate frequency data could be collected. A more current pulse on recent interest in dude using Google Trends shows dude holding a steady interest over a 12-month period (see fig. 2).

According to Google, “interest over time” is defined as: “Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means there was not enough data for this term” (Google Trends). For future research, further investigation can be done to establish dude’s current state of existence, especially as it relates to its function in social interaction amongst same and mixed-gender groups.

This preliminary data suggests dude continues to remain a steady presence in modern language usage. Stephen Clancy’s “The Ascent of Guy” argues that “words like man and dude have long served as exclamations, not really forms of address, or even as specifically masculine referents” (287). As a quasi-genderless address, guy has been unable to shake its first-order group-identity index (men), despite Clancy’s attempts to argue otherwise. Among people, businesses, and institutions who have diversity and inclusion mindsets, guy as a general address is quickly falling out of fashion in favor of more gender-neutral methods of addressing groups. Consequently, while guy loses popularity among a growing number of people, dude continues to flourish. Dude transcends guy. As Hill, Kiesling, and Knoll’s research shows, dude enjoys an array of linguistic capability: it is used by both men and women freely and can address a group of same or mixed genders (Knoll, Kiesling), resets narrative disfluency (Kiesling), builds narrative involvement (Kiesling), expresses emotion ranging from excitement to disappointment (Kiesling, Hill), negotiates conflict (Kiesling), marks affiliation and connection with peers (Kiesling, Hill), and signals agreement (Kiesling, Hill). Hill writes, “In the United States, dude has become a vocal tic, a verbal filler on the order of you know? and fuckin’” (326). With its ability to address same or mixed-gender groups, index social relationships, express a range of emotions, mediate conflict, and animate interaction, dude remains an enduring and endearing presence in the American English lexicon.

Works Cited

Clancy, Stephen J. “The Ascent of Guy.” American Speech, vol. 74, no. 3, Autumn 1999, pp. 282-297. Duke University Press, http://www.jstor.org/stable/455646.

“Dude.” Google Books Ngram Viewer. Accessed 25 June 2019. https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=dude&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=15&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2Cdude%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2Cdude%3B%2Cc0

“Dude.” Google Trends. Accessed online 27 June 2019. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?geo=US&q=Dude

Hill, Richard A. “You’ve Come a Long Way, Dude: A History.” American Speech, vol. 69, no. 3, 1994, pp. 321–327. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/455525.

Kiesling, Scott F. “Dude.” American Speech, vol. 79, no. 3, Fall 2004, pp. 281-305. Duke University Press, https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-79-3-281.

Knoll, Robert E. “The Meanings and Suggested Etymologies of ‘Dude’.” American Speech, vol. 27, no. 1, 1952, pp. 20–22. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/453362.

The Big Lebowski. Directed by Joel Coen, Ethan Coen, Polygram Filmed Entertainment. 6 March. 1998.