Chapter 2: Rhetorical Context: Creating Habitual User/Consumers to be an Advertising Monolith

Each social media platform is a rhetorical context with particular content that influences how its users interact and behave within that platform. This influence occurs because platforms intentionally create conditions via their interface and algorithm that affect a user’s way of participating in-platform. These conditions influence behavior, facilitate interaction, encourage engagement, and induce new, desired behaviors. As researchers Edwards and Gelms note, platforms wield considerable power over their users while simultaneously attempting to obscure that power:

Although platforms host and circulate content they do not produce, it would be a mistake to see them as mere intermediaries. Platforms grant access, but they also set the conditions for that access. Platforms promise to be catalysts for public participation, but they also mask their role in facilitating or occluding that participation. Platforms make decisions, but they often downplay, obfuscate, and/or black box those decisions. (3)

These conditions described by Edwards and Gelms establish a rhetorical context: a platform and its subsequent conditions (user experiences, interfaces, feature designs, or algorithm) that are strategically designed to influence a user’s way of being, doing, and participating to increase their engagement and time spent in-platform. Further, this rhetorical context is designed to drive users to consistently provide information via their interactions in-platform—implicitly or explicitly.

This information, as author Wendy Hui Kyong Chun defines in Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media, is habit and is embedded in culture—the way algorithms are embedded in digital platforms (3). Habits are repetitive actions that over time become automatic—ingrained into our way of existing (6). And through this manipulation of information, habitual users are created and platforms like Instagram are able to teach users to perform the desired action to receive the desired response. For example, if a user posts a picture to their Instagram Feed of their dog and receives several “likes” and comments from other users, this will create a pleasure reaction. This pleasure reaction creates a cycle: post, get engagement, feel happy, repeat. Through creating habit, Instagram creates a consistently active and predictive user experience within its rhetorical context. Understanding Instagram as a rhetorical context and how behavior and engagement occurs, builds an understanding of how advertising elements are adapted for those users within that context.

Key Characteristics of Instagram’s Platform: Explained

Instagram is a visually dominant photo- and video-sharing social media platform. This distinguishes it from other social media platforms and enables it to design a very “brandable” experience for both users and advertisers. When users open the Instagram app, they will see a screen with options to: see Posts in their news feed, see Stories, check their Stories notifications and Direct Messages, create a Story, create a Post, search the explore page, check their Post notifications, and visit their profile (see Appendix B). Authentic (non-sponsored or non-advertising) content created by Instagram users is defined as user-generated content. The following platform characteristics explain how this user-generated content is designed, viewed, and interacted with by other Instagram users.

Instagram Posts & Feed

On Instagram, users can share and view content that appears in a scrollable, vertical Instagram Feed. Content that appears within the Feed is denoted as a “Post”, which can be comprised of photos, videos, and “carousels”. A carousel is a mix of up to 10 photos and videos in a single Post that a user can swipe through (Constine). All visual media is displayed in an 1080px by 1080px square shape specific to Instagram. Videos can range from 3-60 seconds long.

These content Posts are typically accompanied by some form of caption. Captions can vary in “style” and length, depending on the user. For example, some users insert emoji-only captions, while others write long-form captions. Under each Post, users can see two lines of the caption. If the caption is longer, a user can tap “more” to expand the entire caption. Additionally, users can add filters, tag friends or locations, and add captions to their Posts.

This Feed, as described by Instagram, is a “place where you can share and connect with the people and things you care about. In addition to seeing content from people and hashtags you follow, you may also see suggested accounts that are relevant to your interests” (“How Instagram’s Feed Works”). Of course, among these Posts, a user will also see ads. These ads appear roughly every fourth or fifth post. How these ads function within Instagram as a rhetorical context will be discussed further in Chapter 3. This display order of Posts and ads is dictated by an algorithm and user engagement.

Users Interaction & Engagement with Feed Media

In Instagram’s specific rhetorical context, user engagement is defined as an action a user can take to indicate interaction with Instagram-specific content or another Instagram user has occurred. Users have a variety of action options at their disposal to indicate engagement with Feed content or other users in their Feed. Primarily, users can scroll through Posts in their Feed, read short captions or tap “more” to expand long captions, heart (“liking” a Post), comment, swipe through photos/videos or carousel if a multi-media post. Users can “like” a Post by tapping the heart icon or double tapping the Post itself. They also can comment on the Post, send the Post to other user(s) and/or add to their Story, and save to a “Collection”. Saving to a Collection adds Posts to a Collections folder (accessible via a user’s profile) to look at later. Additionally, they can also tap a “…” menu to:

- Report a Post for inappropriate content

- Copy a link to a Post

- Externally share the Post (i.e., send outside of Instagram, in a text message or email, etc)

- Turn on Post notifications to be alerted via notification on your mobile phone when that user posts

- Mute the users’ Posts and/or Stories (follow them but not see their content in your Feed or Stories)

- Unfollow the user

In the comments section, users can like other comments and reply to them as well. Likes, comments, and saves are all engagement actions Instagram uses to calculate interaction with content and other users on its platform.

Instagram Stories

Instagram also includes Stories which appear in a horizontal bar above the Feed (see Appendix B). A “Story” can be a photo, video, text, design that appears full screen for users and is viewable for 24 hours after it’s posted. A new Story is indicated by a highlighted ring around a user’s profile photo. To view the Story, a user simply taps the profile picture icon. Converse to the scrollable, vertical experience of posts, Stories are swipable and/or tappable in a horizontal feed and are ranked via an algorithm similar to Feed posts. However, within an individual user’s Story, Stories appear in chronological order. Stories are timed (roughly 5-6 seconds) to move users automatically though Story content. Similar to Posts, Stories are also mutable.

Stories have become increasingly popular amongst Instagram users as they offer a variety of content creation and design tools: pictures; videos; filters; text options (different fonts, colors, sizing); image options (gifs, emojis, digital stickers); tags (location, users, hashtags) music (attaching a song and lyrics to your Story), and doodles. As an example, the chapter heading images in this study were created using Instagram Stories (background and text) and then overlaid onto a phone icon using design software. Additionally, users can insert Polls to solicit responses from their followers, a Questions box so their followers can ask a question or submit an answer to a question, Quizzes, Countdowns, Ratings, and—the list goes on. Suffice to say, Stories offer an array of creative elements for users to curate their desired Story design (see Appendix C).

User Interaction & Engagement with Story Media

As defined earlier, engagement within Instagram is defined as an action a user can take to indicate interaction has occurred with content or another user. For Stories, users have a variety of interaction and engagement options. Once users tap to view a Story, Instagram will automatically move them through all new Stories. However, user’s can move through Stories by tapping on the side of their phone screen (left tap will move a user backward through a Story; right tap will move a user forward through a Story). To prevent the Story from automatically moving to the next, a user can press their thumb down on the screen to “hold” a post in place to read the content. To move from one individual’s set of Stories to the next, users swipe right. User reactions to Stories are primarily private (versus the public nature of Post reactions). One reples via direct message (DM) and can also react with GIFs or “Quick React” emojis (see Appendix C).

Just as with Posts, among these Stories, a user will also see ads. These ads appear betweenuser Stories (roughly two Stories)—so ads do not disrupt individual’s Stories themselves but appear between sets of Stories.

Instagram Algorithm

While the exact factors that constitute Instagram’s algorithm will never be truly known, in general, social media algorithms are recommendation-based (The Social Dilemma). This means that Feed content is shown in a ‘priority’ order based on what user-content an individual has shown to engage and interact with more. According to Instagram, “When you open Instagram or refresh your feed, the photos and videos we think you care about most will appear towards the top of your feed” (“How Instagram’s Feed Works”). As of 2020, the Instagram algorithm reportedly ranks Posts based on three primary factors: relationship, interest, and timeliness (Cooper). For example, if a user “likes” or comments on a friend’s posts, they are more likely to see that friend’s posts first in their Feed, as this shows a strong personal relationship factor. If a user frequently “likes” recipes from a food blogger who posts new recipes daily, this demonstrates strong interest and timeliness, so food blogger posts are more likely to rank higher in that user’s Feed. Conversely, if Aunt Kathy posts photos of her garden only once a month—and a user rarely interact with their Aunt’s posts—she’ll likely remain lower in the algorithm pecking order. Essentially, these “relationship, interest, and timeliness” signals want to rank content users are most likely to engage with first, so a user is encouraged to keep returning to the platform, scrolling, engaging with content, and interacting with users.

Stories, too, are ranked and prioritized via an algorithm. This algorithm reportedly factors in the same metrics of the Feed algorithm: relationship, interest, and timeliness. Again, the more often users engage with someone’s Stories, how frequently the user posts, and how Instagram reads the relationships between users, the more likely content is to rank earlier in a user’s Stories feed.

No Links Allowed

Arguably one of the most distinguishing features of Instagram is its lack of functionality around hyperlinks—a link that users can click and redirects users to a different website or page. The capability to insert a link into a social media post is a basic, almost throwaway feature on most social media platforms. However, in contrast to other social media platforms—like Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn—Instagram does not allow most users to embed active links in either its Stories or Feed. This feature has led to Instagram-specific “Swipe Up” mechanism available only to specific subset of Instagram users or advertisers. “Verified” Instagram users (denoted with a blue check mark) or users who have +10,000 followers can insert links in their Stories via a “Swipe Up” mechanism. For example, if a verified YouTube content creator posts a video on YouTube and wants to encourage their followers to watch, they can make an Instagram Story with their hyperlinked using the “Swipe Up” mechanism to direct users to their external content.

The only place users can provide an external link is in a single link in their Instagram profile (or “bio”). The reason behind this move remains a point of contention and speculation amongst users. There are those who hate the inability to insert hyperlinks, and there are those who appreciate it. For example, in “’Link in Bio’ Keeps Instagram Nice”, writer Alexis C. Madrigal argues that no external linking was a strategic move on behalf of Instagram to “never become a full participant in the web. By refusing to allow hyperlinks, it has maintained a distinct space on the internet” (Madrigal). However, the real reason behind Instagram’s “no links” policy is covertly embedded in Rob Meyer’s similar piece, “I Like Instagram”:

It is a silly, idiosyncratic piece of software, but so simple. It says: Here is a picture. Here is a picture of a weird bird my friend saw. Here is a picture of my friend celebrating Eid with her brother. Here is a picture of an acquaintance flying over the city where I used to live.

With every photo, I have two options. I can scroll by, or I can say “I saw this and liked it.” Either way, then I scroll some more. It is a place to look at pictures and, maybe, video. It does not do much else. It doesn’t need to. It is so simple as to be almost serene. (Meyer)

Meyer’s reverence of Instagram inadvertently stumbles upon the more likely reason for this emulation of serenity: a mechanism of rhetorical context to keep users scrolling.

When users are not pulled away from the platform by outbound links they stay in the platform as engaged, active users. This engagement is the driving force behind the success of social media networks as ad revenue drivers (The Social Dilemma). When habitual users are consistently in-platform engaging with content, they are habitually primed consumers that can be targeted with ads.

Instagram’s ability to design a rhetorical context extends influence over its users and its advertisers. Users scroll through Posts or swipe through Stories. They like, comment, and share Posts and follow, tag, message other accounts. They design Stories and swipe, tap, hold, comment, and react to other user’s Stories. All this user behavior provides intel and data on Instagram users which can be monetized by Instagram via in-platform advertising. Instagram users can now be targeted as consumers. And where there are consumers, there’s money to be made.

Instagram as an Advertising Monolith

Instagram’s ability to create a rhetorical context that keeps habitual users in-platform is critical for its advertising revenue. When it has users to whom it can show ads, it generates social media advertising revenue (income earned from advertisers using Instagram as an advertising platform). Financially, advertising is an important facet of Instagram, and Instagram is equally as important to advertisers. Understanding how significantly valuable Instagram advertising is provides key insight into why Instagram endeavors to have a rhetorical context. Further, it’s advantageous for advertisers to leverage that rhetorical context as it relates to creating Instagram-specific advertising content amongst Instagram user-generated content.

As an industry, advertising earns a significant amount of national and global revenue from persuading consumers to buy products, goods, or services online. The U.S. is one of the largest advertising industries in the world: It accounts for 38% of the world’s total value in advertising revenue and reported total revenue earnings of $225.5 billion in 2019. (MarketLine 8). To earn revenue, advertising agencies or agents display promotional content (advertisements) across a variety of platforms and media—like television, print, and digital ads—with the ultimate goal to persuade consumers to purchase products, goods, or services.

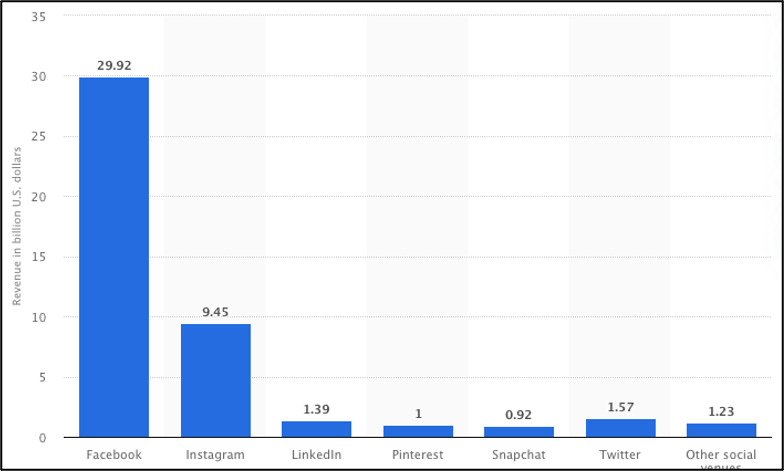

Increasingly, social media advertising makes up a staggering portion of U.S. ad revenue. In 2019, Facebook and Instagram accounted for $40 billion dollars in ad revenue (see fig. 2)—runaway leaders in the category of social media revenue by platform (Guttman). In 2019, Instagram alone accounted for $9.5 billion in revenue dollars for the U.S. It comes in second only to Facebook (its parent company), with the next-nearest competitor being LinkedIn, at $1.4 billion.

The success of social media advertising for platforms like Instagram stem from the widespread improvement and access to internet services, increase in smartphone users, and increase in time spent on smartphones (MarketLine 8). According to market research, 77% of the U.S. population owns a smartphone and the average time spent on that smartphone is 90 minutes a day (MarketLine 18). As a result of far-reaching internet and smartphone access and time spent using smartphones, social media apps like Instagram are increasingly popular in usage—Instagram, for example, has 1.2 million active users on its platform (Clement).

Accordingly, Instagram is an attractive advertising channel for singularly accessing a large number of consumers and targeting desired demographics. It collects collects data and information from habitual users via its rhetorical context who can then be targeted as consumers. This stronghold on understanding who consumers are and where and how they spend their time is financially beneficial for Instagram: advertisers only dedicate ad spend (budget allotted to advertising) to lucrative advertising channels for their products or services. And Instagram has the data to deliver the goods.

An example how Instagram can be successful in demographic targeting is millennials (MarketLine 9). Millennials are an oft-discussed demographic in terms of their tech adoption: 93% of millennials own smartphones (Vogels). Additionally, as population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate, millennials have surpassed Baby Boomers as the nation’s largest living adult generation—making them the largest adult consumer popular (Fry). In conjunction with their widespread use and adoption of smartphones, millennials are a prime demographic for Instagram usage—and Instagram advertising. D2C advertisers can use Instagram to market to them and a large portion of adult consumers. Thus, as millennials with access to smartphones largely overtake prime adult consumer population, it is increasingly important for advertisers to successfully target them via Instagram.

As a result of a large consumer base and data available for demographic targeting, for the first time ever, ad spend dedicated to social media advertising overtook print advertising in 2019 and became the third largest advertising channel, behind television (29%) and paid search (17%) (Zenith). And the more Instagram proves to be a worthy channel of successful targeting consumers with ads, the more ad revenue it earns. Accordingly, for Instagram, it is important to continue creating a rhetorical context that increases their habitual user/consumers. It also means the better Instagram is at a creating that rhetorical context, the more likely it is to gain ad spend over other social media (or any) platforms. Inherently, this continually drives up the value of Instagram’s platform and its users/consumers.

Instagram earns ad revenue by monetizing its users and their time: the more time a user spends in-platform, engaging and interacting with user-generated content, performing desired behaviors, and implicitly providing data based on these behaviors, the more Instagram can influence them as consumers. Additionally, with $9.5 billion in generated ad revenue, Instagram has demonstrated its ability to successfully sway both user behavior and advertising behavior. The dexterity to produce platform conditions which extend influence over user engagement and consumer engagement influences advertising elements because brands must appeal to user/consumers within that rhetorical context.